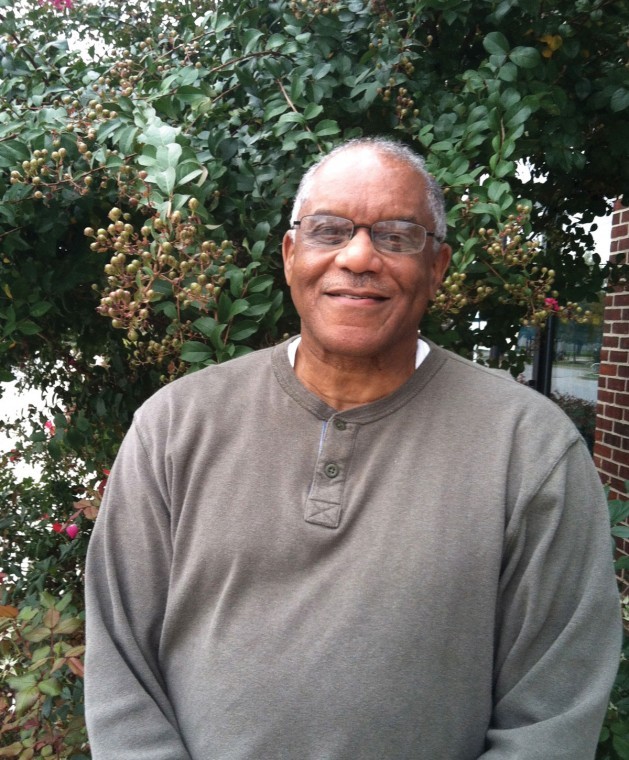

Sylvester Woolford People you should know

This article includes parts of a larger article available here.

Sylvester Woolford will be our guest speaker at the October 8th Town Hall: : The Journey from Shirley Bulah to Rudy Bridges. He will talk about the 80 Schools for black children that Pierre Dupont built over 100 years ago when Delaware would not provide education to black children. He has been involved in the restoration and preservation of several of these schools around Delaware.

Woolford’s passion for researching history was inspired by his own family’s past and later extended much beyond his own lineage. His study of historical U.S. Census data, land records, death records, deeds, newspapers and other sources has helped him put together a detailed portrait of what life has been like for black Americans in Delaware before, during, and far beyond the Civil War.

Stories of people like Mary Francis Bacchus, a slave in Middletown who, according to death records, died in 1861 at age 4 from “softening of bones,” help us remember – and hopefully learn from – some of the more somber truths of our state’s history, he said.

Growing Up

He was born in 1943 to Sylvester and Grace Saunders Woolford, and grew up with his parents and sister, Lelia, in a house on New London Avenue in downtown Newark.

“At the time, I had a mother and father and five aunts and uncles who all lived on New London and Corbett Streets,” he said.

He attended New London School, the Newark High School for two years and in junior year, transferred to William Penn when his father, a teacher at the Buttonwoods School, moved the family to New Castle.

He said as a child, he was not allowed to go beyond the New London community because, being black, he would not have been welcome on Main Street or other areas of downtown.

Still, he said, his childhood was quite normal.

My parents used to push you out the door in the morning and say ‘Come back when you’re hungry,’” Woolford recently recalled. “Within the community, it was a very safe community. We played with each other, football, basketball and baseball all day long. We were so insulated (that) we didn’t know they were poor; it was only four blocks. You couldn’t go out of the neighborhood (because of the segregation,) so the greatest thrill in life was when the ice-cream truck came by and rang its bell.”

The Journey to History

Woolford earned a bachelor’s degree in business administration and accounting from Delaware State University and then a master’s degree in business administration from Rutgers University. Going on to work for many years in accounting and sales with such firms as Campbell Soup, IBM, Pacific Telesis and Sun Information Services. Most recently he worked for, and retired from, AAA MidAtantic in Wilmington.

He said he didn’t develop an intense interest in history until after he retired, in 2008, when the City of Newark published the book “Histories of Newark: 1758 – 2008,” in honor of the city’s 250th anniversary.

“They did a fantastic job on it, and left my family out of it,” Woolford said.

The book’s authors did a tremendous job of recounting the city’s history, particularly its industrial evolution, he said.

“But I thought there were some missing people and they left out the schoolteachers,” he said. “There was not one African-American schoolteacher mentioned in the book.”

The slight stung a little, but it inspired in Woolford a resolve to research his own roots. He started simply searching family members’ names on Google, and searching online databases for historical records. He eventually culminated a trove of information about black Delawareans.

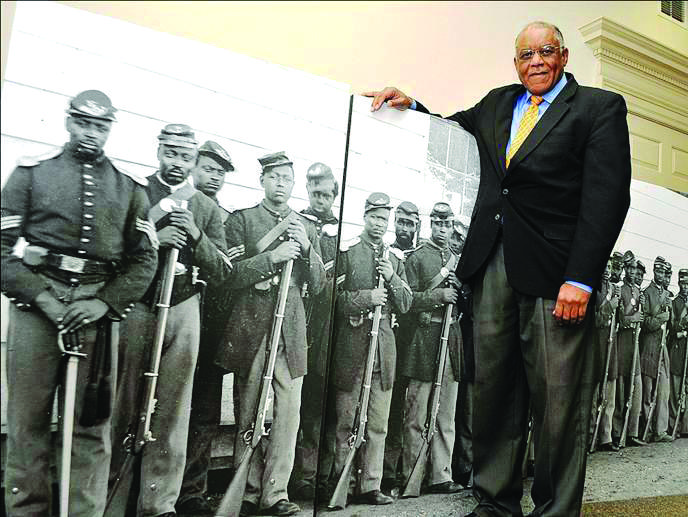

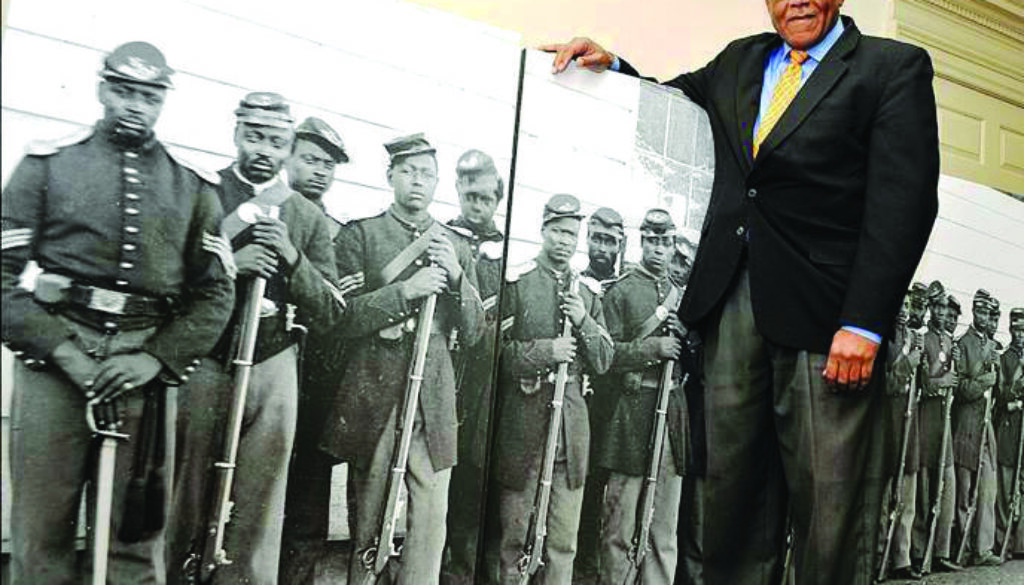

He has since poured his research into PowerPoint presentations, and has recently lectured to audiences around the state on topics including U.S. colored troops who fought in the Civil War; Methodism among blacks in the 18th and 19th centuries; advertisements for slaves that ran in Delaware newspapers; the legacy of Howard High School; and black patriots and loyalists during the War of 1812. This Monday at Kirkwood Highway Library, he will lead a discussion on the genealogy of Newark’s Iron Hill Community.

He has also already booked several black-history presentations throughout the state during the month of February.

He noted the statue recently erected at Tubman-Garrett Park in Wilmington, co-honoring Harriett Tubman, the noted slave, and Thomas Garrett, the white landowner credited with helping to free scores of slaves in this area.

“Suddenly, the Underground Railroad is about white folks helping black folks escape slavery,” Woolford said.

Woolford invited anyone interested in having him host a lecture, or learning about upcoming lectures in the area, to contact him at sylwlf@aol.com.

Why this is so relevant to me is, there’s a debate and a million dollars on the table to establish an African-American heritage center in Wilmington, and the question is, (in the establishment of such centers,) can white folks write black history, or does it get whitewashed?” Woolford said. “In my opinion, it does get whitewashed.”

This article includes parts of a larger article available here.