How the First Black Female Jockey Rode Into Oblivion

By Sarah Maslin Nir | May 28, 2021 | Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/28/sports/horse-racing/black-woman-jockey-horse-racing.html

Fifty years ago, Cheryl White became America’s first licensed Black female jockey when she was just 17 years old. So why doesn’t the world know her name?

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio — It was an average June morning in 1971 at Thistledown Race Track in North Randall, Ohio, when an average bay filly named Ace Reward broke from the gate. But still, the stands were packed, and the finish line bristled with news crews.

Sitting astride Ace Reward was Cheryl White, who soon would become the country’s first ever licensed Black female jockey, in her first official race. After an ambitious sprint, the filly finished dead last. The crowd roared anyway.

White was on her way to making history. And she was a 17-year-old girl.

On an average morning 50 years later, at another Ohio track, White’s name was again on the leader board, this time in memoriam, at a race in her honor. She died of a heart attack in 2019, at age 65.

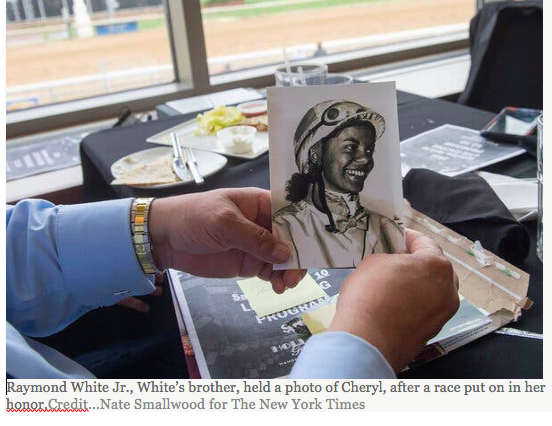

But few in the thin crowd craning at the thoroughbreds at Mahoning Valley Race Course, in Youngstown, had ever heard her once-storied name, the one drowned out by hoofbeats as it crackled from the loudspeaker. Few had paid much heed as her family stepped into the winners’ circle to hand the victorious jockey the Cheryl White memorial trophy.

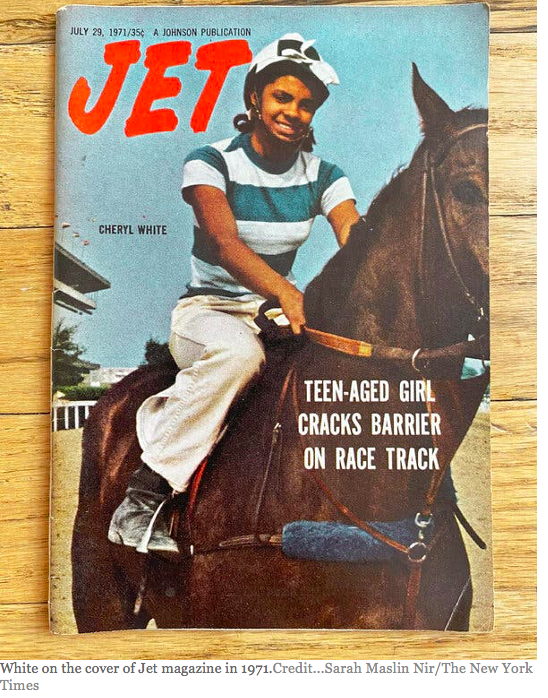

The single-minded Black teenager intent on racetrack glory was a phenomenon in her day, interviewed in newspapers and on TV and featured on the hit quiz show “What’s My Line.” Curls escaping from her helmet, she beamed from the cover of the July 29, 1971, edition of Jet magazine, the headline splashed across her horse’s chest: “Teen-Aged Girl Cracks Barrier on Race Track.”

“I just wanted those gates to open,” White told a reporter for BetChicago shortly before she died, about that day in June 1971. She meant the starting gates. For those who watched her ride, White opened many more.

But today, White’s story is not one of enduring triumph but of continued marginalization. The girl whose horses’ hooves beat a path for women and Black people in a sport that has historically sidelined both is virtually unknown. And her accomplishments — a more than two-decades-long career included 750 winning rides in several disciplines, according to White’s own estimates — are largely forgotten.

Search for the jockey Cheryl White in Google and the picture of another Black female jockey, Sylvia Harris, comes up beside her name. A GoFundMe page created by her brother, Raymond White Jr., to honor “a true American Legend!” with a foundation to support other riders of color, has raised just over $2,100, in two years.

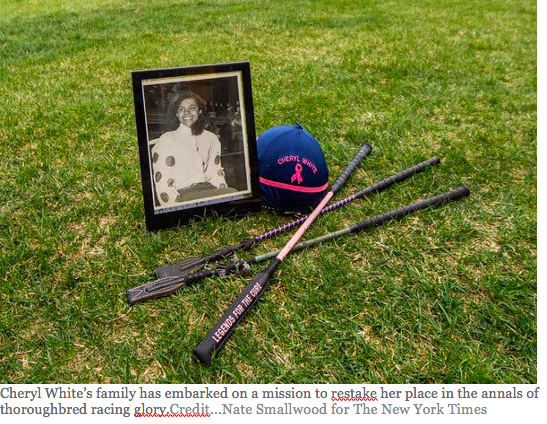

It’s crushing for White’s family, which has embarked on a mission to restake her place in the annals of thoroughbred racing glory.

“Whenever I hear about icons and she’s never mentioned, I don’t know why,” Raymond White III, her nephew, said. “It makes you hesitate to think it’s rooted in racism. It almost feels like it’s the cheap answer — but it’s the answer.”

‘Her Talent Was Huge’

White’s career was comfortable, studded with firsts. Soon after her probationary ride on Ace Reward, race stewards awarded White her coveted jockey license. That September, railbirds at Waterford Park in West Virginia witnessed the improbable vision of the 5-foot-3, 107-pound high school student cleaving from the pack astride a chestnut gelding named Jetolara to become the first Black woman to ever win a race in America.

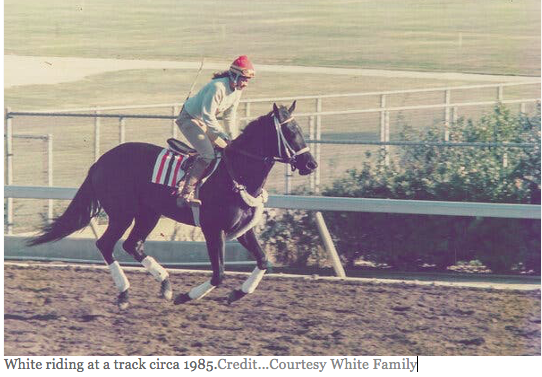

Her riding career spanned two decades. She amassed 227 wins and earnings of $762,624 riding blood horses, moved to California in the mid-’70s and later took up the county fair sport of Appaloosa horse racing.

After injuries forced her retirement in the early ’90s, White worked as a racing steward in California, becoming perhaps the first Black woman to have the role in the state, according to racing historians. She was the first woman to win the Appaloosa Horse Club’s Jockey of the Year award, not once, but four separate times, earning her induction into its Hall of Fame in 2011.

Those parochial accolades do not satisfy her fans, friends and family who struggle to understand why White’s name, instead of being inscribed in the public consciousness alongside greats like the track star Jackie Joyner-Kersee and the tennis star Serena Williams, ended up instead mangled by Google and largely forgotten in thoroughbred racing. It was even misspelled on the glass trophy her family was invited to present at her memorial race.

The reasons they give span from the particular — White was loath to self-promote, equipped with a cantankerous personality and a temper as swift as a mare’s kick — to the pragmatic: White came to rue her career move to head West, where the tracks were small-time, and where, she said in interviews, she felt her race and gender made it even more challenging to get quality mounts.

But above all, they feel systemic issues are at fault: “It was not lack of talent — her talent was huge,” said Jessica Whitehead, the curator of collections at the Kentucky Derby Museum, which features White in “Right to Ride,” a temporary exhibit on female jockeys. “It was lack of opportunity.”

White was an athlete in a sport that has been late and slow to not just fully admit

Black jockeys were aboard 13 of the 15 horses that competed in the first ever Derby in 1875. Go back further, and at its nascence, the entire industry was predicated on the labor of enslaved Black people. Many were purchased from West Africa specifically for their equestrian skills to be its riders, trainers and grooms.

In American racing’s earliest days, owners ran the horses they owned with the humans they owned atop them.

A Lot of Reckoning to Do’

In the modern era, Black people, and women, comprise a vanishingly small percentage of the sport. According to data maintained by the Jockeys’ Guild, the union that represents more than 95 percent of jockeys in North America, just 7 percent of its 950 active members are female. The guild does not ask about ethnicity or race on its membership applications.

Terence J. Meyocks, the guild’s president and chief executive officer, blamed the dearth of Black jockeys on the insular way many riders enter the sport: It is often passed down through families, Meyocks said, and there are few Black racing families in the first place.

The Jockey Club, which supervises the breed registry, does not have a single Black person among its 126 members and has just four people of color among its 261 employees.

Diversifying the sport, Meyocks said, is not strictly the responsibility of its institutions, but up to those women and Black people who have managed to blaze a trail: “Once they do well, that’s what’s going to get people’s attention; young Black kids looking up to them to be heroes and role models,” he said.

The changes underway in other sports, such as baseball and basketball, where teams have participated in boycotts or removed names and mascots seen as offensive, have barely begun in horse racing.

“Horse racing has a lot of reckoning to do just by the nature of how the sport began and how important enslaved Africans were to the development of the sport,” said Whitehead, the Derby museum curator. “Like our entire country, there is a lot of unlearning that has to be done from decades and decades and decades of misinformation and suppression of certain story lines.”

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/28/sports/horse-racing/black-woman-jockey-horse-racing.html